Southeast Asia Buzz List 2025; Trump Tariffs; Thailand’s New Funding

On Wednesday, US President Donald Trump announced a set of global tariffs that make little economic sense and sent stock markets plummeting. At least they make little economic sense unless Trump and his billionaire buddies are planning to buy the dip in anticipation of a big stock market rally, but it increasingly looks like there’s no plan with this administration – just vengeance, vanity and wanton self-destruction.

Asia, in particular China and Southeast Asia, will be among the economies hardest hit by the tariffs. While it’s too early to say how this will affect the region’s content industries, many Asian consumers were already fearful about spending on leisure goods and services and the economic fallout from Trump’s tariffs is not likely to give them much more confidence.

The irony is that, with the exception of China, Asia has not protected its content industries from US domination in the streaming era and Asian companies are not exporting a huge amount of content to the US. We currently have a situation in which an American company, Netflix, has created a close to feudal content production system in several Asian countries, where local filmmakers now have few options but to toil for Netflix on local-language production, but most of the profits are flowing back to the US. It’s unclear whether these contradictions fit into Trump’s concept of a trade deficit.

Then there are the English-speaking territories, Australia and New Zealand, where US companies are producing a large volume of films and streaming series, but not investing heavily in local content. Australia has pushed back against this and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has promised to hold steady on plans to introduce local content rules for global streamers, despite objections from the US (Deadline’s Max Goldbart has written some analysis on potential impact of the tariffs on international industries including Australia here).

Meanwhile, US productions are able to tap into generous incentives funded by public money in Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan and now Japan, where the government recently renewed its 50% rebate scheme for another year. Trump may insist this production now stays at home, but Hollywood may be the real loser, especially as global audiences appear to be losing interest in American stories. In future, stories focused on characters and countries outside the US are likely to gain a wider international audience and it may be challenging to film those in California.

Film and streaming policies are unlikely to be top of the agenda as governments around the world formulate a response to the tariffs but now may be a good time for them to think about how to support their local content industries.

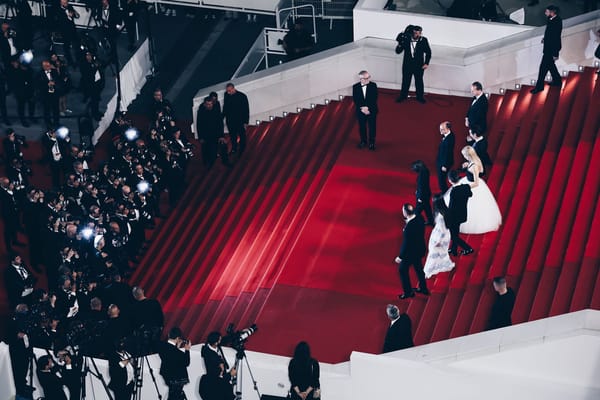

As the world was reeling from Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’, Streamlined was compiling the 2025 edition of its annual Southeast Asia Buzz List, which reveals that despite policy changes that may reduce or redeploy public film funding across Asia, creativity remains high in the region and there are several projects that are contenders for Cannes and other festivals later in the year. The region also has a new source of funding from the Thai government. Below are are a few notes on both, along with the link to Southeast Asia Projects In The Pipeline 2025.

BUZZ LIST: Southeast Asia Projects In The Pipeline 2025

Several sources of public funding in Southeast Asia have become less consistent over the past few years, as agencies including Singapore’s IMDA, Taiwan’s TAICCA and the Film Development Council of the Philippines shift direction and try to figure out what they should be supporting. Streamlined Guides is researching this topic and aims to publish a report before Cannes, so welcomes any insight from producers who are dealing with these agencies.

In the meantime, Streamlined’s Southeast Asia Buzz List 2025 highlights some of the projects in development, production and post-production across the region, with a focus on co-productions, of which there are still many. It’s also interesting to see Southeast Asian producers getting involved in co-productions with other parts of Asia, including Aakash Chhabra’s I Will Smile In September, a co-production between India’s Crawling Angel Films and Singapore-based Akanga Film Asia, and Chie Hayakawa’s Renoir, a co-production between Japan, France and Singapore (again Akanga Film Asia). There are also an increasing number of collaborations between the Philippines and the US and Canada.

To read the rest of this article, subscribe to the ‘Streamlined’ newsletter: STREAMLINED